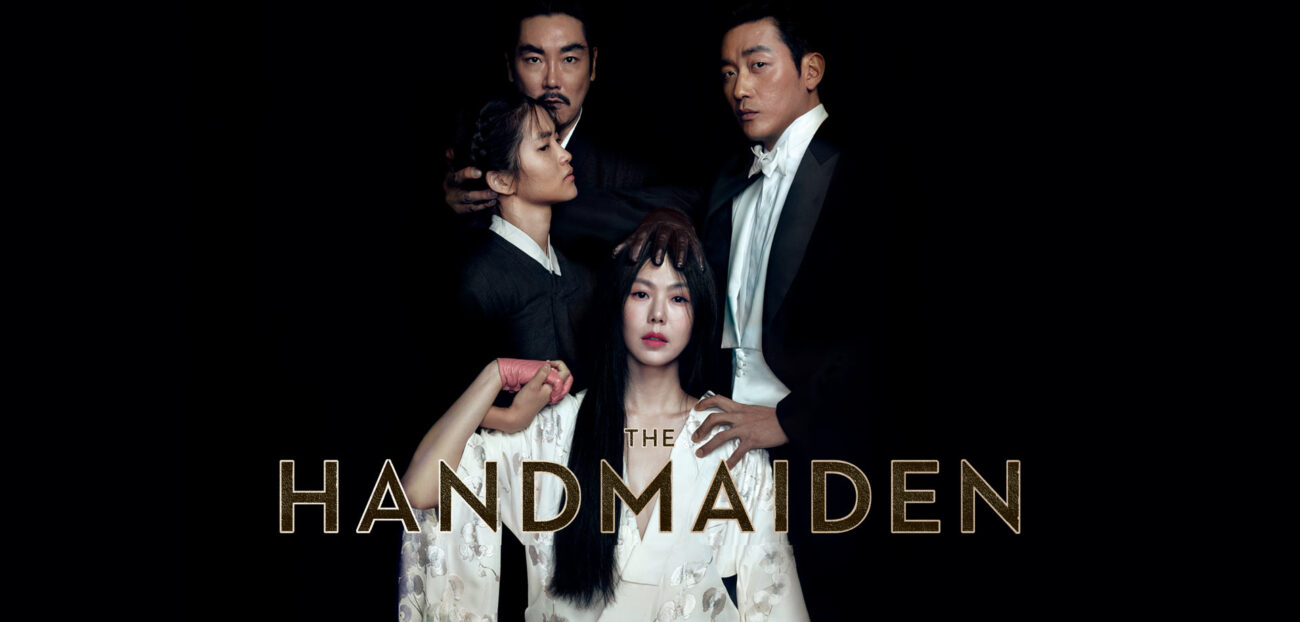

The Handmaiden: A Cinematic Masterpiece

by: Jin Bongcac of Marvill Digital Presence

A lavish narrative of changing identities, forbidden love, and colonialism is featured in Park Chan-wook’s latest romantic thriller. This masterpiece created by an award-winning Korean director, Park Chan-wook has gained tons of recognitions internationally, and even awarded in the prestigious Cannes Film Festival.

image source: CJ Entertainment

The Handmaiden is a multifaceted work that combines a lavish historical romance with a sensual spy thriller complete with double-crosses and hidden identities. This deep psychological horror by Park Chan-wook, one of the genre’s masters, is a lengthy meditation on Japan’s rule of Korea in the 1930s. The Handmaiden is a dazzling, horrifying tale of love and treachery that layers on opulent images while never losing sight of its human-centered core. But more than anything, it is just great cinema. The film feels like an evolutionary step in Park’s already outstanding career as a filmmaker of crossover genre smashes like Old Boy and Thirst.

In comparison to rope play, Park Chan-Wook’s adaptation of Sarah Waters’s well-known book Fingersmith clocks in at just under three hours and is kinky, knotted, and purposefully deferred fulfillment. Waters’s queer, corset-ripping historical drama is moved to Japanese-occupied 1930s Korea in the skilled and crafty hands of co-writers Chan-Wook and Seo-kyeong Jeong, with the class and gender tensions of the Victorian original viewed through a colonial prism. Tae-ri Kim and Min-hee Kim, the two female leads, seek to cross and double-cross each other from the other side of this chasm, only to fall in love in the process.

image source: CJ Entertainment

Tae-ri portrays Sook-hee, a thief from Korea who is hired by Jung-woo Ha’s sleazy Korean conman. He assures Sook-hee that they will pose as Count Fujiwara, a Japanese-born suitor, and Tamako, a handmaiden, in order to defraud Lady Hideko, the haunting character played by Min-hee Kim, of her inheritance. The goal is to use Tamako as a wing lady to court, elope with, and then institutionalize Hideko. However, as we will see, there is more to this gambit than Sook-hee is aware of.

Before Fujiwara can move in on his prey, Jin-woong Jo’s Kouzuki, Hideko’s harsh, perverse, and equally cunning uncle, needs to warm up to him. Kouziki, a Korean farmhand who married his way into the nobility and is now passing himself off as Japanese-born, is another dishonest social climber like Fujiwara. And like Fujiwara, he also wants Hideko’s inheritance. In a home full of monsters, including the Danvers-like housekeeper Sasaki and the basement “pet,” this wicked patriarch is king and rules over Hideko with a cruel, evil hand. However, unknowingly to him, a revolt is brewing: Hideko, we later learn, is not the innocent, defenseless aristocrat Tamako has fallen for, but rather a desperate and cunning abuse victim who is fostering her own hidden emotions and schemes.

image source: CJ Entertainment

The Handmaiden appears to be a seductive examination of dualism and code-switching, a performance using the rules of society to elevate the few and oppress the rest. It is a reflection on sexuality, power, and performance. But it’s also a magnificently dark homage to women’s liberty and desire, a topic that is just as urgent today as it was a century ago.

The story in the movie is delivered in three parts from three separate perspectives, much like in the book, and the same events take on new significance with each telling. The repetition has a fetishistic, compulsive quality similar to Kouzuki’s desire for books and Tamako’s obsession with feminine finery, including fine jewelry, lace lingerie, scented baths, and her mistress’s sweet-sour kisses. The convoluted matrix of family and home, with its closed network of roles and scripts and intergenerational dynamics.

image source: CJ Entertainment

Admire Tamako’s sword-wielding, snake-smashing Furie during the wonderful devastation of Kouziki’s filthy library, and observe the glorious hatred Hideko has for Fujiwara during the kimono-tying post-marriage scene, preferring a knife handle to her new husband’s touch. When Fujiwara becomes discouraged by his female conspirator’s seemingly unfathomable feelings, the joke is on males and their cocksure myopia, not on women.

These are strong jokes done for feminism’s sake. In Hideko, the cold, nearly ghostly girl of the gothic 19th-century sensation novels is not the asylum angel or the insane woman in the attic but rather the frighteningly sane survivor in the basement, cheating her way to freedom one act at a time. While Sook-hee’s Tamako is endearingly gauche, Min-lee’s Hideko is a model of graceful cunning, deftly flitting between the roles of pale ingénue, painted geisha, and drag-sporting strategist. We awe at her cunning, not as evidence of female cunning but of our hard-won multiplicity—a necessary survival skill in a world that expects excellence from us in every endeavor.

image source: CJ Entertainment

It’s a valid argument, but ultimately unpersuasive. Nothing in this movie feels pure or without purpose in a world so full of social conflicts, from class and gender to sexuality and ethnicity. In the last scene, Chan-Wook makes an effort to put a stop to these concerns with a stylized symmetry, but paradoxically, this simply reveals his own need for order and his charitable but naive perception of queer female love as some sort of classless utopia.

Happily, this scene’s out-of-the-ordinary quality only strengthens the eerily magical quality of the lovers’ triumph. This happy ending is made all the more poignant given that death is always present, whether it be in the form of the lethal vial of poison Hideko carries to protect herself from her uncle’s basement or the eerie family heirloom she keeps lovingly hidden away in a hat box. Death might befall the couple—doesn’t it usually happen when queer women are shown in media? – but only to reunite them after being revealed under the cherry blossom tree during a soul-wrenching night. Death kills in an aesthetically pleasingly brutal way, taking the men. Together, Hideko and Tamako survive—a swift and deserved victory.

image source: CJ Entertainment

It’s exhilarating to watch Park maintain control of the film’s shifting tone as well as to watch the characters turn on one another since The Handmaiden’s identity varies as much as its sinuous ensemble. This is fundamentally a story of emancipation, of removing masks, and of the joy (and terror) that comes with accepting one’s actual nature. To say much more would ruin a stunning ending. The Handmaiden won’t appeal to everyone because it is lengthy, occasionally insane, and quite intense. However, filmmaking is what demands attention since it’s a thrilling experience that serves a much greater and more significant purpose.

Let us know your opinion. Leave a comment below.

Visit us at Marvill Webdev to know more!